“No matter what you do, your first 200 sermons will be terrible.” – Tim Keller

How’s that for encouragement?

While it may sound like a bummer, Keller is actually pushing into the freeing reality that it just takes awhile to find your preaching style.

Our goal is to help you find your preaching style — your voice — so that you can be the preacher God made you to be.

The main thing you need to find your voice is time. As Keller implies, it takes a bunch of reps. But you can also learn a lot from studying the styles of effective preachers and pulling from the best of what you learn.

Ultimately, your church doesn’t need you to preach like Matt Chandler, Mike Todd, DawnChere Wilkerson, Steven Furtick, or Andy Stanley. They need you to preach like YOU.

How do you figure out your preaching style?

It begins with considering what preaching styles are and why they exist.

What Preaching Styles Are

When we talk about preaching styles, we’re looking at the different ways that sermons sound, feel, and are structured.

While the word ‘style’ can be used to describe things that seem superficially cosmetic, we want to explore preaching styles in a more thoughtful way.

The New Oxford American Dictionary defines ‘style’ in a few ways:

- a manner of doing something (different styles of management): a way of painting, writing, composing, building, etc., characteristic of a particular period, place, person, or movement (the concerto is composed in a neoclassical style); a way of using language (he never wrote in a journalistic style); a way of behaving or approaching a situation that is characteristic of or favored by a particular person (backing out isn’t my style).

- a distinctive appearance, typically determined by the principles according to which something is designed (the pillars are no exception to the general style).

Applied to sermons, we could define preaching style as a preacher’s typical manner of communicating biblical truth (taking into account structural, verbal, non-verbal, and experiential habits) to a congregation.

More than defining preaching styles, however, we know them when we see them. Sermons are intellectual, emotional, and spiritual, so preaching styles naturally interact with all three areas.

Preaching Styles to Avoid

While all of us have different opinions about preaching that resonates with us, some preaching styles should be avoided. These are ways of communicating the Bible that are not helpful and will lead to diminished effectiveness.

Whether because of poor structure or poor delivery, here are ten preaching styles to avoid.

1. The “Look at Me” Preacher

This preacher makes the sermon about the preacher. While this is rarely done explicitly, the end result is that the listener is left more impacted by the preacher than the Lord.

This almost always comes from the preacher’s insecurity and takes different forms.

Sometimes it looks like a preacher sharing too many stories about himself — especially ones that paint him as the hero of the story. Other times this comes from the preacher trying to be too self-indulgent with humor, drama, or boldness.

As preachers, our goal is to point to Jesus, not ourselves.

2. The “Comedian” Preacher

Related to the “Look at Me” preacher is the “Comedian” preacher. Now, humor is a remarkable gift from God and part of his good creation. Many church folks will likely be surprised in the eternal kingdom when they experience how funny Jesus actually is.

Humor is especially valuable when it comes to preaching. It helps relieve tension, keeps people engaged, makes the preacher relatable, and lowers people’s resistance to tough truth — as long as it’s not used as a weapon.

But humor can also really distract from the focus of preaching if there’s too much of it. If the listener’s main response after the sermon is, “Wow, that preacher was so funny,” it may have crossed a line.

3. The “Bible Commentary” Preacher

Another unhelpful style is the preacher who acts like he or she is reading a Bible commentary. This is often long and detailed, working through each verse with many word studies in the original languages, long commentary quotes, and rabbit trails into different interpretive choices.

These kinds of details can be helpful and important, but only when used sparingly. “Bible Commentary” preachers often misunderstand exegetical preaching, and feel compelled to share as much of their homework as possible.

When listeners suggest that expository preaching is boring, this is usually what they mean. Expository preaching can be thrilling (we’ll tell you more about how to do that below), and these preachers give it a bad name.

“It’s a sin to bore people with the Bible,” preaching professor Haddon Robinson famously said. He’s right.

4. The “Rubber Chicken” Preacher

In a similar, but slightly different way, another unhelpful style is the “Rubber Chicken” preacher. This name comes from the chicken that is often served at banquets, fundraisers, and weddings — it’s way overcooked and tastes rubbery and tough.

This preacher has spent a ton of time studying and preparing (which is good), but very little time editing (which is bad). As a result, the sermon just has way too much in it.

The communication may be great, and the content included may be helpful. But you know you’ve done a “Rubber Chicken” sermon when, at the end of it you think, “That sermon would have been a good series.”

5. The “Microwave” Preacher

On the opposite end of the spectrum is the “Microwave” preacher, who is simply throwing together whatever he or she can as fast as possible. If the “Rubber Chicken” preacher overcooks the sermon, the “Microwave” preacher habitually undercooks it.

We’re not talking about what happens when you get asked to fill in at the last minute for a preacher who has fallen ill. This is a style of preaching that is regularly unprepared and under-developed.

This is a special challenge for bi-vocational preachers who are faithfully working another job and preparing a spiritual meal each Sunday, but even full-time pastors can fall prey to just winging it.

In the end, we have to ask ourselves whether we gave the best preparation we could in the time we had. If not, we’re likely microwaving our sermons, which will likely lead to under-nourished congregations.

6. The “Aimless Driving” Preacher

Kids can handle a long trip in the car if they have a sense of where they’re going and what the stops along the way will be like. Without this, the trip turns into kids constantly asking “Are we there yet?”

It can be the same when listening to “Aimless Driving” preachers. These sermons just seem to meander along with no clear sense of direction. They are hard to follow and end up incoherent.

Not every sermon needs a three-point outline stated at the beginning, but every sermon needs some kind of structure that keeps it progressing.

We don’t like movies that seem to wander aimlessly, and few people would enjoy a car trip with no sense of destination. In the same way, rambling sermons leave listeners mostly hoping the trip will end as soon as possible.

7. The “Talking to Myself” Preacher

This preacher is so what he is saying, and often so tied to his notes that if everyone in the room vanished, he would just keep preaching.

Rather than trying to really connect with the listeners, it can be easy for a preacher to begin to enjoy hearing himself or herself speak. But this must not be the approach for us as faithful preachers.

We must seek to have our sermons connect with people where they are, and teach them as much by how we connect with them as what we say.

8. The “Bueller, Bueller” Preacher

It’s pretty dated now, but some readers will recall Ben Stein’s role as a teacher in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, taking attendance with monotony and boredom. Preachers must never sound like this.

Of course it’s rare to hear a preacher who is actually that monotone and boring. Often the “Bueller, Bueller” preacher sounds like somebody who is very passionate and just stays revved up for the entirety of the sermon. It leaves listeners feeling tired.

Preachers need to learn appropriate voice inflection, vocal dynamics, the use of strategic pauses, and other “gear changes” that help communication stay interesting. This is usually accomplished by listening to or watching yourself, or by seeking honest input from a trusted coach.

9. The “Yelling” Preacher

Related to the previous point, a preaching style that is often ineffective is the “Yelling” preacher. While there is an appropriate time to get fired up in the pulpit, we ought not to come across as mostly angry.

Constant yelling makes a preacher sound outraged and emotionally unstable. There will always be some gluttons for punishment who like this kind of “telling it to me straight.” But for most people, hearing constant yelling will grow wearisome.

10. The “Hammer” Preacher

Have you heard the saying, “To a hammer, everything is a nail”?

That’s the idea of the “Hammer” preacher. This is the preacher who, no matter the biblical text or topic, always brings it back to the same thing—their version of a nail—in the same way. Usually he or she is caught up in some particular hobby horse that always makes its way into the sermon.

To be clear, we’re not talking about preachers who skillfully connect every sermon with Jesus. That’s what great preachers do. But we have to be careful that our sermons don’t end up actually sounding the same because we constantly go back to the same issues in the same way.

A Better Way: Finding Your Best Preaching Style

Having explored some unhelpful styles of preaching, let’s consider a better approach to preaching that will lead to far greater fruitfulness in ministry.

To find your best preaching style, you need to have a key conviction, and then find the structure and voice that best fit who you are and the context you’re ministering in.

A Key Conviction: To Say What God Says

There’s a good chance that the reason you got into preaching wasn’t because you sensed in yourself some unique insight on the world that everyone needed to hear.

Rather, you’re a preacher because you’ve been saved by a great and gracious Savior and you want the world to know how much better life could be with him.

You believe that “All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable” (2 Timothy 3:16), that “the word of God is living and active” (Hebrews 4:12), and that even if the grass withers and the flowers fade, “the word of the Lord remains forever” (1 Peter 1:25).

So, we want to encourage you in a conviction you may already have: to preach in such a way that the point of your sermon comes from the passages of the Bible in your sermons.

We don’t want to use the Bible to say what we think.

We want to preach the Bible to say what God thinks.

This is called “expository preaching.”

And, in this sense, we hope every preacher is an expository preacher.

When people hear the phrase “expository preaching,” they often confuse it with what is sometimes called sequential preaching, where the preacher walks through a portion of scripture verse-by-verse.

But expository preaching is simply letting the text of Scripture create the point(s) of the sermon. It’s “exposing” the meaning of the text to the hearers.

Definitions of expository preaching abound, and Erik Raymond helpfully provides some of these definitions from expository preachers who have written on the subject.

John MacArthur: The message finds its sole source in Scripture. The message is extracted from Scripture through careful exegesis. The message preparation correctly interprets Scripture in its normal sense and its context. The message clearly explains the original God-intended meaning of Scripture. The message applies the Scriptural meaning for today. (Preaching)

Bryan Chappell: The main idea of an expository sermon on the topic, the divisions of that idea, main points, and the development of those divisions, all come from truths the text itself contains. No significant portion of the text is ignored. In other words, expositors willingly stay within the boundaries of the text and do not leave until they have surveyed its entirety with its hearers. (Christ-Centered Preaching)

John Stott: Exposition refers to the content of the sermon (biblical truth) rather than its style (a running commentary). To expound Scripture is to bring out of the text what is there and expose it to view. The expositor opens what appears to be closed, makes plain what is obscure, unravels what is knotted, and unfolds what is tightly packed. (Between Two Worlds)

Alistair Begg: Unfolding the text of Scripture in such a way that makes contact with the listeners world while exalting Christ and confronting them with the need for action. (Preaching for God’s Glory)

Haddon Robinson: The communication of a biblical concept derived from and transmitted through a historical-grammatical and literary study of a passage in its context, which the Holy Spirit first applies to the personality and experience of the preacher then through him to hearers. (Biblical Preaching)

David Helm: Expositional preaching is empowered preaching that rightfully submits the shape and emphasis of the sermon to the shape and emphasis of a biblical text. (Expositional Preaching)

John Piper: Expository exultation. (The Supremacy of God in Preaching)

Albert Mohler: Expository preaching is that mode of Christian preaching that takes as its central purpose the presentation and application of the text of the Bible . . . all other issues and concerns are subordinated to the central task of presenting the biblical text. (He Is Not Silent: Preaching in a Postmodern World)

Mark Dever: Expositional preaching is preaching in which the main point of the biblical text being considered becomes the main point of the sermon being preached. (Preach: Theology Meets Practice)

Tim Keller: Expository preaching grounds the message in the text so that all the sermon’s points are the points in the text, and it majors in the texts’s major ideas. It aligns the interpretation of the text with the doctrinal truths of the rest of the Bible (being sensitive to systematic theology). And it always situates the passage within the Bible’s narrative, showing how Christ is the final fulfillment of the text’s theme (being sensitive to biblical theology). (Preaching: Communicating Faith in an Age of Skepticism)

Notice that none of these definitions are about the structure of the sermon. They do not emphasize that expository preaching must be sequential or verse-by-verse through a biblical book.

Rather, expository preaching is about a conviction more than a style. John Stott’s definition makes this distinction: “Exposition refers to the content of the sermon (biblical truth) rather than its style (a running commentary).”

You may be thinking, “Yes! That’s what I want! To say what God says… but how do I figure that out?”

We’re here to help.

The First Step in Expository Preaching

The starting point for expository preaching is understanding the text of Scripture. Paul instructs Timothy to, “Do your best to present yourself to God as one approved, a worker who has no need to be ashamed, rightly handling the word of truth” (2 Timothy 2:15).

How do we do this?

1. Start with Prayer

Prayer must certainly be part of how a preacher walks with God. But prayer must also be a crucial part of interpreting the Scriptures.

The Bible is a “God-breathed” book and, thus, cannot simply be read scientifically or analytically.

To be sure, we cannot interpret correctly without good reading techniques. But it is possible to read well and still come short of God’s message—especially if we read without the Spirit’s help. Prayer must be part of the process, from beginning to end.

2. Get to Know the Biblical Story

In order to rightly understand a biblical text, we must know the larger story of which it is a part. This means not only must we know the larger context of the book in which the text is situated, but also the overall biblical story.

There are multiple ways to summarize this biblical story, but one of the most helpful is found in The Drama of Scripture by Michael Goheen and Craig Bartholomew. They describe the Bible as a story taking place over six acts:

Act 1: God Establishes His Kingdom (Creation)

God made everything good, and made human beings in his image. Adam and Eve flourished in the Garden of Eden, walking closely with God, having intimacy with each other, feeling comfortable in their own skin, and joyfully stewarding the creation.

Act 2: Rebellion in the Kingdom (Fall)

Despite God’s presence and care for Adam and Eve, they distrusted his heart and rebelled against him. The consequences were severe and far-reaching. Instead of closeness to God, they hid from him.

Instead of intimacy with each other, they blamed. Instead of being comfortable in their own skin, they knew they were naked. Instead of joyfully stewarding creation, they experienced toil and curse.

Act 3: The King Chooses Israel (Redemption Initiated)

Most of the Hebrew Scriptures describe God’s work to initiate redemption. Beginning with Abraham, God chooses a people who will experience his blessing for the sake of all nations.

Abraham’s descendants, the people of Israel, experience God’s rescue from Egypt, receive God’s instruction, and are called to be a light to the nations. They continually struggle with idolatry and experience the consequences of sin, but God remains faithful to them.

Act 4: The Coming of the King (Redemption Accomplished)

Despite some moments of obedience, Israel largely failed to be a faithful light to the nations because of their own indwelling sin. God sent his Son Jesus to be the Second Adam and True Israelite, and Jesus succeeded where they failed.

In his divinity, Jesus shows us how far God was willing to go to win back his people. In his humanity, Jesus shows us what trust and obedience look like.

Jesus announced and demonstrated that the kingdom of God was at hand, lived a faithful life of love and obedience to God, died a sinner’s death as a substitute for sinners, rose from the dead, and sent his Spirit to inaugurate the Age to Come and empower his people for mission.

Act 5: Spreading the News of the King (The Mission of the Church)

The gospel message is news, not advice. So the church, empowered by the Spirit, now heralds this news to the world. In word and deed, the church community is a foretaste of the kingdom of God and a contrast community to the world.

She is an ambassador of Christ, challenging the idolatry of human culture and persons while also pleading with sinners to repent and trust in the risen Lord Jesus.

Act 6: The Return of the King (Redemption Accomplished)

The kingdom of God is consummated with the return of Jesus and the establishment of the New Heavens and Earth. Jesus’ redemptive work will spread into all creation “as far as the curse is found,” and all things will be made new.

3. Pay Attention to What the Structure is Saying

Not only do the words of Scripture communicate meaning, but often the literary structure communicates as well.

Correctly understanding the Bible requires considering what the structure might be saying. Here are some examples of how the structure of the biblical text provides interpretive insight:

- James. Without understanding literary structure, the book of James is remarkably confusing. If we read it in a typically linear fashion, we find ourselves confused about how the author moved from one topic to the next. But a study of the literary structure reveals that James is written much more as wisdom literature, where chapter 1 introduces the key themes and words and then the rest of the book explores these themes that are relevant to all Christians everywhere.

- Job’s friends. In Job 4-25, Job’s friend makes a simple argument: bad things happen to bad people (which contradicts what the reader knows by reading the first two chapters). There are three cycles of the friends condemning Job. Each speaker in each cycle gets progressively less eloquent, and each speech gets progressively shorter (Zophar, the third friend, doesn’t even make his final argument). This structure helps communicate that the friends, though sincere, have an unsound argument.

- Mark 8:22-10:52. Mark’s gospel is not like a clipping together of raw security camera footage of the life of Jesus, but rather like an expert documentary filmmaker crafting the footage into a compelling story. One example of this is in 8:22-10:52, where Jesus’ healing of two blind men serves as bookends to a section about seeing Jesus. In the first (8:22-26), Jesus heals a blind man in Bethsaida. Unlike his usual healings, Jesus heals this man in stages:

Mark 8:23–25 / And he took the blind man by the hand and led him out of the village, and when he had spit on his eyes and laid his hands on him, he asked him, “Do you see anything?” And he looked up and said, “I see people, but they look like trees, walking.” Then Jesus laid his hands on his eyes again; and he opened his eyes, his sight was restored, and he saw everything clearly.

This ‘in stages’ healing is a picture of how people are starting to see Jesus, but not quite clearly. In the very next story, in fact, Peter will confess Jesus as the Christ (yay!) and then immediately rebuke his plan to suffer (no!).

Peter, like the blind man, can see—but not clearly. The next few chapters describe many people, especially the disciples, straining to see who Jesus really is and how he came to suffer.

The second healing, of blind Bartimaeus, concludes this section (10:46-52). In the section just prior, James and John are jockeying for positions of greatness. But then it’s the blind beggar asking “Jesus, Son of David” for mercy.

In tremendous irony, the blind man is the only one who “sees” Jesus.

This theme continues throughout Mark—everyone who should be able to see Jesus can’t and everyone who shouldn’t be able to see him can. Indeed, as the gospel concludes, it is the Roman centurion who ironically declares, “Surely this man was the Son of God” (15:39).

- Lamentations 3. Here the prophet is lamenting the fall of Jerusalem with emotion and grief. At first read of the English text, it seems that the prophet is ranting with things one ought not say to God.

But a study of the literary structure of the Hebrew text reveals that this chapter is an acrostic, where each three verses begins with a new letter of the Hebrew alphabet (see photo).

So, these laments are not some kind emotional, flying-off-the-handle. Rather, they are finely crafted, artistic expressions of grief. This teaches us that it is good and godly to give sustained thought and expression to our pain and loss.

The structure communicates.

4. Read Carefully.

This may seem obvious, but many Christians (and even pastors) get tripped up here.

A preacher must spend significant time absorbing the context, situation, and words of Scripture. Casual, careless reading leads to thin preaching.

Additionally, the questions we bring to the text will shape what we get out of the text.

As we study God’s word, we should ask and answer a number of questions (whether in our heads or in writing) that force us to seriously engage the text of Scripture:

- What observations do I have of the passage?

- What initial impressions do I have of the passage?

- What are the key words, verbs, and themes in this passage?

- What cultural dynamics need deeper understanding or exploration?

- How would I rewrite the passage in my own words?

- What emotions are described or drawn out from this passage?

- What is the basic point of the passage?

- Why is it important?

- Why do we resist this truth?

- What about this passage highlights the fallen condition that all humanity faces? (See Bryan Chapell’s Christ Centered Preaching for more on what he calls the “Fallen Condition Focus”)

- How is Jesus and/or the gospel communicated through this text?

- What does the text want people to know, feel, and/or do?

5. Engage in Communal ‘Listening’ to the Text Early in the Process

One drawback to the individualistic mindset of Western culture is that we can neglect the communal nature of interpreting Scripture.

God uses the beautiful plurality of his church to help us read well—seeing and hearing insights that can only come from the diversity of experience, background, culture, stage of life, moment in history, theological tradition, and gender.

We should leverage two sources in particular:

- Trusted believers in the local community. The model of a solitary preacher holed up in her study is foolish. Find a group of people to discuss the text with.

Some preachers may develop a formal group who meets regularly for this purpose, while others may need to be intentional about seeking input from others in their local church. Not only will this help the preacher better interpret Scripture, but it will also give increased insight into how to apply the Scriptures to her local congregation.

- Commentaries. What a gift we have in commentaries! Through remarkable technology, we are afforded the opportunity to ‘listen in’ to many wise (and some foolish) interpreters from a variety of situations and settings.

In many cases, these interpreters have been able to spend the majority of their lives investigating the Scriptures and preserving their insights as a gift to the church.

Every preacher would be well served to have at least a few single-volume commentaries on the whole Bible, like the ESV Study Bible, New Bible Commentary, or Bible Knowledge Commentary.

If you have financial ability to purchase commentaries, check out https://www.bestcommentaries.com/ to find recommendations on each book of the Bible.

If finances are limited, you can still find helpful resources at Blue Letter Bible, Dr. Constable’s notes, or Precept Austin.

Though conventional wisdom encourages preachers to use commentaries at the end of the process (as a kind of ‘check’ on your work), it might be wise to consult commentaries earlier in the process. If God has given his Spirit to his people, then leveraging their wisdom and insights early in the process seems important.

Also, it saves a bunch of time to ‘check your work’ early in the process. If you’re headed in the wrong direction, wouldn’t you rather find that out at the beginning than the end?

6. Enter Into the Story From Multiple Angles

The best storytellers help the listener not just hear the story, but experience it. Similarly, some of the richest preaching helps the listener experience the text.

This kind of preaching and storytelling is possible. But in order to lead others into experiencing the text, the preacher must experience it first. He or she must truly enter the story—not simply skimming off the top, but walking in the sandals of those involved.

In his preaching workshop, master storyteller Chris Brown encourages preachers to look at the text through multiple angles—using the example of David and Goliath:

- What would this text feel like for the main characters involved? How would Goliath have felt as he looked out to see a shepherd boy? What would it have been like for David to be trouncing around in Saul’s armor? What emotions might David have felt as he heard Goliath mock his God?

- What would this text feel like for the surrounding characters? What was it like to be an Israelite soldier and hear the daily taunts? How might the Philistine army have felt about having such a powerful warrior like Goliath? What did Jesse think would happen once David arrived with food for his brothers? What was going through Saul’s head?

- What would this text feel like for those who would be affected by the situation? What would the wives of the Israelites have been thinking during the time their husbands were off to war? What kinds of prayers might have been offered by the children of these fighting men?

This approach to reading Scripture can provide some remarkable illustrations and even introductions (Brown very effectively begins most of his sermons with a story that leverages this kind of ‘sanctified imagination’).

Whether these insights ever make it into the sermon, they help the preacher enter into the text in a powerful way.

7. Bring the Crucial Truths Into The Sermon

Once you’ve read and understood the passage under consideration, you’re ready to bring it into the sermon.

Expository Preaching Examples

There are a number of preachers who are exceptionally strong at expository preaching.

- John Piper is doggedly committed to communicating what the truth of the text is saying. He even has an approach to digging into Scripture called Look at the Book.

- Charlie Dates is masterful at bringing out the truths of Scripture. Not only are his sermons a good example of this, but he also contributed to a tremendous book, Say It!, about expository preaching in the African American tradition.

- Jen Wilkin is a tremendous Bible teacher who, through her books and Bible studies, relentlessly pushes Christians to study with their hearts and minds.

- Mark Dever is a skilled expositor and has also written a helpful book, Preach: Theology Meets Practice.

- Andy Stanley is not likely thought of as a “typical” expositor, but he’s very good at bringing out the truth of Scripture from a passage and also has a helpful book, Communicating for a Change.

Having considered a starting point and some examples of a key conviction, we now turn to discerning the structure you want to use in discovering your voice as a preacher.

Determining Your Structure

Armed with the conviction that you want to say what God says—and the ability to discern what that is, we want to help you think through the structure and voice that will help you develop your best possible preaching style.

There are multiple ways to structure your sermons, each with strengths and weaknesses.

Structure #1: Exegetical Preaching (i.e., Verse-by-Verse Preaching)

Many tremendous preachers prefer to preach sequentially through books of the Bible or passages of Scripture — often called “exegetical” preaching or “sequential” preaching.

“Exegetical” comes from the Greek word exegesis, meaning “to lead out.” Exegesis brings out of the text what’s there. This contrasts with eisegesis (“to lead into”), where the interpreter or preacher injects his or her own ideas into the text.

As we’ve said, in one sense all preaching should be exegetical and expository. But in another sense, exegetical preaching tends to be more like a math student who “shows her work,” making plain to the listener where the conclusions came from.

Sequential preachers tend to preach longer series based on books of the Bible, though the length of the series varies based on the book and the preference of the preacher.

Preachers who often preach sequentially: Matt Chandler, Mark Clark, John Piper, Beth Moore, Larry Osborne & Chris Brown, Jen Wilkin, Tim Keller, Tony Evans.

Strengths of Sequential/Exegetical Preaching

- It communicates in a structural way that we are listening to God’s word and that the Bible is setting the agenda. As said above, all good preaching is expositional. But sequential preaching makes it more clear that the preacher isn’t making stuff up.

- It forces you to preach on parts of the Bible you would likely never choose. Many books of the Bible have something that would be easier to skip. Sequential preaching forces you to address issues that are difficult to embrace, understand, or believe.

- Similarly, sequential preaching often feels deeper and richer to listeners because they are exposed to the entirety of thought from a particular book.

- It teaches people to study the Bible for themselves. When done well, listeners get a model for how to read and understand the Scripture. They see the connective tissue between passages, and marvel at God’s word rather than the creativity of the preacher.

- It’s easier for the preacher. Instead of a preacher having to be super creative in dreaming up a topical series, the preacher gets to follow the flow of the text. Additionally, the preacher saves a bunch of research time from not having to dig into the background in fresh ways each week.

- It can expose the congregation, over time, to the whole counsel of God. The Scriptures have lots of variety and by preaching various books the church can get a broader taste of how God speaks to his people.

Weaknesses of Sequential/Exegetical Preaching

- It can lead to a lack of creativity. It doesn’t have to, but because of the ease of sequential preaching and a commonly held idea that “because it’s God’s word people should care,” some verse-by-verse preachers aren’t as creative as they should be.

- It can feel monotonous. Most Bible books only have a few big themes, so long series through one book can start to feel repetitive — especially if you interpret it correctly.

- It leads you into a number of sermons that don’t feel particularly relevant to most people. While most of Romans feels quickly applicable, it’s difficult to make Romans 9-11 feel so relevant. This isn’t saying that Romans 9-11 can’t be applicable — just that it takes some work for the preacher to help people want to lean in and engage.

- Ironically, it can keep the congregation from the whole counsel of God (in contrast to #5 above). Sometimes preachers organize sequential series to be so long that they get bogged down in one book for multiple years. Especially in transient communities, this can make it hard for people to get a balanced spiritual diet.

Structure #2: Topical Preaching

Likely the most popular structure for preachers today is topical preaching or thematic preaching. Whereas sequential preaching begins by moving consecutively through a book of the Bible, topical preaching starts with a topic or theme.

Topical preaching often consists of shorter series (often 4-6 weeks and rarely longer than 12), and are often approached with creativity and engaging branding.

Some well-known preachers who mostly preach topically are Andy Stanley, Mike Todd, Sadie Robertson, Steven Furtick, Louie Giglio, Christine Caine, Judah Smith, Levi Lusko, and Rick Warren.

There are multiple ways to approach topical preaching. We could call the two main methods systematic theology and passage based.

Systematic Theology Topical Preaching

This approach starts with a topic or theme and looks to multiple passages of scripture where the theme is addressed (this is the approach in many popular systematic theology books).

For example, a preacher might want to preach a message on the Holy Spirit and incorporate John 3, Acts 2, Acts 5, and Romans 8 into one sermon — pulling truths about the Holy Spirit from the breadth of Scripture.

Passage Based Topical Preaching

This approach also begins with a topic or theme, but generally limits the sermon content to one specific passage. In this approach, the topic of the Holy Spirit might be addressed by preaching through John 14:15-31.

Andy Stanley and Levi Lusko do this exceptionally well, usually limiting the sermon to one passage and mining it for significant content.

Strengths of Topical Preaching

- Topical preaching is often experienced as highly relevant. Of course, this depends on the topic, but most topical preachers tend to select themes that their congregation needs or wants to learn more about.

- The topical approach imitates the approach of the New Testament epistles. In each of Paul’s letters he is addressing issues specifically relevant to the audience, while still being able to share content (for example, Colossians and Ephesians share many themes).

- Topical preaching allows the preacher to teach more in-depth about a particular theme. In consecutive preaching, the sermon is mostly limited to the focus of that passage and then the preacher moves on. But in topical preaching, the series can allow the preacher to inspect the issue from multiple angles.

- Topical preaching helps non-Christians make clear connections about the Bible’s relevance for today. In a world where many non-Christians assume the irrelevance of Scripture, this approach can raise very contemporary questions and then answer them with the truth.

- Because topical series are often shorter, they can be easily repurposed for on-demand content related to specific issues. When people have questions about certain issues, these archives provide an easily accessible format for the sermon to outlive the day it is preached.

Weaknesses of Topical Preaching

- Topical preaching can allow important biblical truths to remain unexplored. While sequential preaching forces a preacher to address uncomfortable issues, topical preaching can be highly selective. As a result, important but unpopular truths may be ignored.

- Topical preaching can exhaust the preacher or church staff by requiring a great deal of creativity to organize and execute. Because the series and sermons can go so many directions, creative people thrive. But many churches wear themselves out trying to “outdo” their last amazingly relevant series.

- Topical preaching can unintentionally undermine the congregation’s confidence in their ability to study the Bible. This is particularly true in the systematic theology approach, where the preacher pulls in passages right and left and the listener is left thinking, “How did he do that? I could never understand this Bible.”

- In a systematic theology approach to topical preaching, the individual sermon may not be particularly deep. This often comes from a preacher not wanting to study three or four texts in depth (pulling out commentaries, doing word studies, etc.).

Structure #3: Topi-getical Preaching

A third structure is not well known and may not have a name, so we’ll call it “Topi-getical” preaching. As you might guess, this comes when you combine topical and exegetical (or sequential) preaching.

In this approach, the preacher will often begin by going sequentially through a passage, but then end up adding systematic theology style content to the back half of the sermon. As a result, these sermons — and series — are often very thorough and quite long.

Two of the more well-known topi-getical preachers are John MacArthur and Mark Driscoll.

This approach minimizes some of the downsides of the sequential and topical structures, but it also leads to very long sermons. Unless you are a world-class communicator or your congregation is very hungry for long sermons, this approach is likely not something you should do much of.

3-Point Sermon?

When we think of structure, we often wonder how many points it must have.

Most sermons tend to be three points. How did that happen?

Well, we’re not sure, though some suggest it has roots in medieval scholasticism.

Three-point sermons are common and popular, and as Brian Jones points out, people all over the world use a three-point structure “to tell stories (beginning. middle. end.), tell jokes (setup. story. punchline.), and craft screenplays (act one. act two. act three.).”

Or maybe it’s because we worship a Triune God? (OK, probably not)

Whatever the reason, there’s no Bible verse commanding a three-point sermon.

The specific structure is less important than the need for the sermon to have cohesion, be easy to follow, and help connect the truth of Scripture with the lives of the hearers.

Your preaching style emerges from the combination of a key conviction (to say what God says), a typical structure (sequential, topical, or topi-getical), and discovering your voice.

Having explored conviction and structure, let’s now consider your voice.

A Preacher’s “Voice”

When we consider the idea of the preacher’s “voice,” we’re not talking about the sound of his physical voice (how deep or high), nor about his accent or verbal tics. Rather, we’re talking about the distinct feel of his preaching and communication.

The preacher’s “voice” is a mixture of how he sounds, his verbal and non-verbal dynamics, his points of emphasis, his point of view, and the other qualities that are distinct to him.

The preacher has found her voice when she is comfortable in her own skin, and not mimicking the styles or convictions of anyone else.

Until a preacher has his voice, he will often sound like a copycat, borrowing phrases, intonation, gestures, or habits of other influential preachers.

Oftentimes, when people talk about somebody’s preaching style, they are really just talking about the preacher’s “voice.”

The Voices of Well-Known Preachers

At the risk of ignoring your favorite preacher or painting with too broad a brush, it may be helpful to consider the voice/style of some well-known preachers.

Tim Keller has a thoughtful, intellectual voice that connects with well-educated secular people. He often quotes literature, philosophy, and non-Christian leaders as a way to build a bridge with non-Christians. He comes across as reserved and highly intentional. He manuscripts his sermons in a strange shorthand, and often stands stationary behind a microphone.

Matt Chandler is passionate. He loves the Bible and gets fired up when he’s explaining it. His witty, sarcastic humor often disarms the audience even though he’s regularly hard on nominal Christians.

Steven Furtick is entertaining and creative. He has a dialogical approach (“turn to your neighbor”) with a flair for the dramatic. Often accompanied by music, he moves almost constantly, sometimes walking into the audience (or pulling them on stage) and interacting with specific people. He is inspirational, moving people to their feet.

Charlie Dates combines head and heart in his preaching. He usually begins in a measured, methodical manner with spikes of passion and volume to a Jesus crescendo toward the end. Preaching mostly from a manuscript, Dates’ words are well-crafted with a call-and-response rhythm emerging from a rich history in the African-American church.

Christine Caine is a strong mix of passionate and straightforward. She frequently uses stories from her past and is fluent in Old Testament illustrations. She inspires big faith as she calls people to reach their God-given potential through Jesus.

Judah Smith focuses on Jesus and has fun doing it. Despite his flamboyant clothes, he seems like a relatable person. The son of a pastor, he leverages his loving childhood home and current family to illustrate his sermons.

Albert Tate is heartfelt and engaging. Quick-witted and funny, he often leverages humor to draw his audience in. He’s also a master storyteller, able to paint pictures with his words. Tate also effectively shares about his own struggles in a way that gives listeners hope.

Beth Moore has faithfully taught the Bible for decades. Known for her women’s Bible studies, she leverages her southern charm and friend-next-door warmth to help listeners experience God’s word in a fresh way.

Levi Lusko combines incredible creativity with detailed attention to the text. He uses humor (especially self-deprecating), props, images — anything to help people engage with God’s word. He’s also very open about the deep pain he and his family have experienced, making him extremely relatable to hurting people.

John Piper passionately exalts the glory of God. Combining textual rigor and heartfelt fervor, he has impacted many pastors and young people over the last three decades. With messages that are finely manuscripted and free from banter, Piper preaches with an urgency that makes you believe that he believes what he’s saying.

Mike Todd is young, fun, and inspiring. Hundreds of thousands of people — especially young people — watch his bold, loud, and unapologetic sermons and highly transparent Instagram posts every week. He’s cool and culturally engaged.

Louie Giglio preaches long but engaging sermons that wonderfully capture the imagination. Giglio is the master of taking an image or illustration and weaving it through an entire sermon. He’s connected to the heart of the next generation, and his wonder of God comes through.

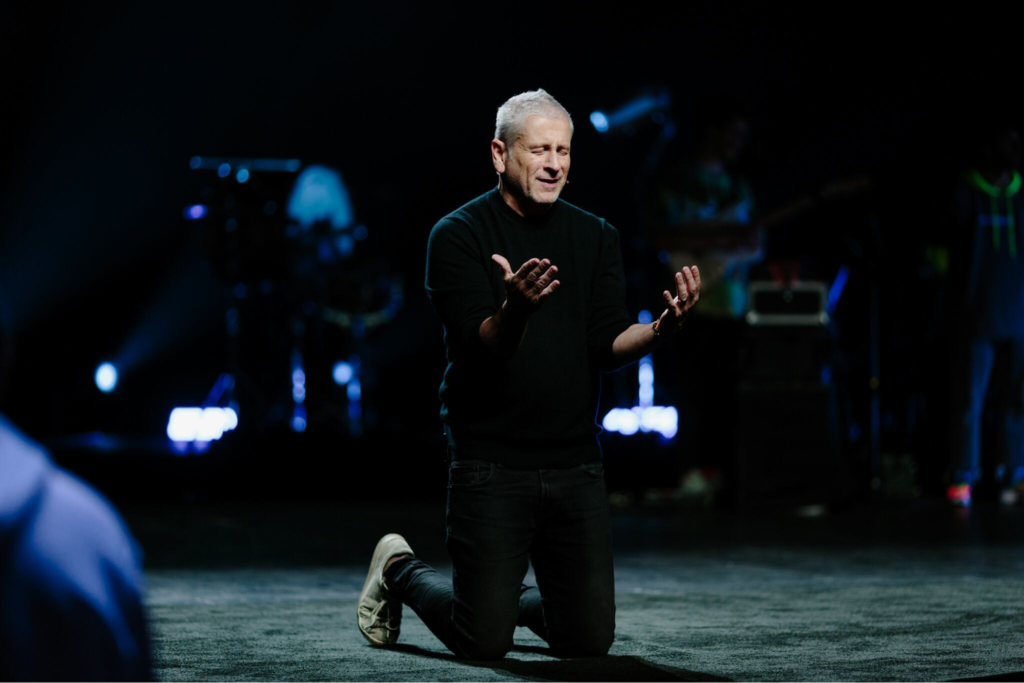

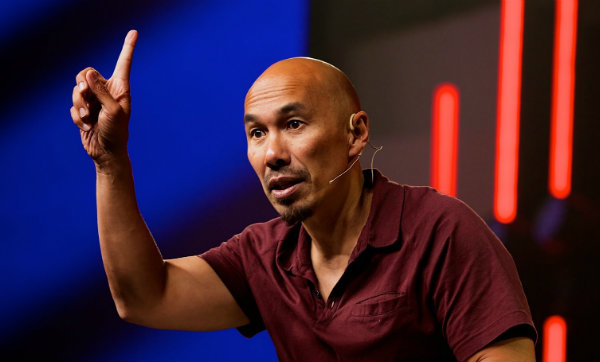

Francis Chan preaches like a man with a burden. He feels deeply about the holiness of God and the responsibility of God’s people to live their faith and it comes through. Like a prophet, he’s unafraid to say the difficult truths, which has inspired the adoration (and scorn) of thousands of people.

Andy Stanley (who went to middle school with Giglio) is a brilliant communicator who excels at making you want to listen. Always preaching with the unchurched person in mind, he exudes wisdom, grace, and thoughtfulness. Rarely using notes, Stanley is able to engage with the audience like few preachers can.

Where Does a Preacher’s Voice Come From?

Preaching voices are like music styles — there are a bunch of them, and not everyone resonates with them in the same way. It’s like this with all communicators.

Consider well-known comedians like Jerry Seinfeld, Chris Rock, Nate Bargatze, Ali Wong, Dave Chappelle, Jim Gaffigan, Amy Schumer, or Brian Regan. They’re all funny, but they all have a distinct voice.

Depending on who you talk to, people may love or hate their comedy. Similarly, we love the styles of certain preachers and don’t care for others.

Some folks love the thoughtful analysis of Tim Keller, while others find it stuffy and too detached.

Others can’t get enough of Rick Warren’s practical preaching, while some find it to be too basic.

When preachers like John Piper or Charlie Dates get fired up it makes some want to shout “Amen!,” while others want to tune out.

Preachers, like musical artists, sound and feel different — and that’s wonderful.

At the same time, however, there aren’t infinite musical styles. We can categorize different artists and songs into different genres. In the same way, there are only so many preaching styles.

Each of these styles come from different places and teach us different things. And, just like a great musician can lean into and borrow from different musical styles, strong preachers can take the best of different styles of preaching and turn it into their own.

Where does a preacher’s style come from? Like music, it usually emerges out of a number of overlapping factors.

Different Personalities

We all have different personalities that shape how we approach life. It makes sense this would influence our preaching. The best preachers allow their personalities to come through their preaching—that’s why it feels authentic—without becoming self-indulgent.

What’s your personality? Are you reserved? Expressive? Funny? Shy? Bold? Confident? Curious? Deferential?

Contrary to many people’s opinions, there is no one best personality for being an effective preacher. But the best preachers are true to their personality.

Different Spiritual Gifts

In 1 Corinthians 12:4-7, the Apostle Paul writes:

Now there are varieties of gifts, but the same Spirit; and there are varieties of service, but the same Lord; and there are varieties of activities, but it is the same God who empowers them all in everyone. To each is given the manifestation of the Spirit for the common good.

In addition to different personalities, preachers have different spiritual gifts that influence their sermons. Some are gifted evangelists, others are gifted leaders, others have gifts of wisdom, teaching, or exhortation.

As a result, the preaching (and often the church or ministry itself) highlights the gifts of the preacher. Evangelistic preachers see many people come to faith, wise preachers see many people have “aha!” moments, and preachers with gifts of faith see many people encouraged through suffering.

As Paul makes clear in 1 Corinthians 12, no single person has all the gifts. So no preacher should aspire to preach as though he or she has them all. Rather, we humbly use the gifts God has given us and let them come through our preaching.

Different Experiences

Rick Warren says that “God never wastes an experience.” If that’s true for all Christians, it should also apply to preachers.

Preachers who grew up in loving, stable homes where they were taught the gospel at an early age usually sound different than those who came to faith as adults after a rough early life.

John Piper and John MacArthur were both sons of traveling evangelists. Was this a factor in them both preaching in one church for multiple decades? Perhaps.

Derwin Gray played for five years in the NFL and, thus, often uses sports analogies and stories.

Levi Lusko tragically lost a young daughter and, as a result, his preaching deeply connects with suffering people.

Andy Stanley and Ed Young, Jr. grew up as the son of large church pastors, so their sermons often have little nuggets of leadership gold.

Ravi Zacharias came to faith while in the hospital after a failed suicide attempt, so his preaching is shaped around giving hopeless people reasons to believe.

It is inevitable that our experiences shape our preaching in significant ways. Preachers ought to lean into it.

Different Theological Sensibilities

Theology shapes preaching styles not merely through the content of the sermons, but also through the approach to preaching. While every Christian preacher would generally agree about core Christian doctrine, differences emerge when you start reflecting on how theological convictions look in action.

John MacArthur esteems theological precision and holds clearly defined convictions around even secondary issues. As a result, he tends to preach in a way that is very concerned with potential errors and often feels combative.

Louie Giglio lives in wonder at the greatness and grandeur of God, and his sermons often highlight the bigness of God, even if he doesn’t provide highly specific application points that correspond.

Jen Wilkin passionately believes in people studying the Bible for themselves. So, in her messages, she frequently insists on the listener closely following along in the Bible.

Preachers can go too far in preaching theological hobby-horses instead of preaching the main idea, but we can’t help but have our theology come through our preaching styles.

Different Passions

It’s been said that, “People don’t remember what you say, but they remember what you get excited about.”

That’s what passion is. It’s the topics or themes that make a preacher come alive in a unique way. It’s the passion a preacher comes back to time and again.

Mike Todd can’t stop talking about how God shapes our relationships. Steven Furtick comes alive when sharing stories of big faith. Louie Giglio is driven to connect with the next generation. Larry Osborne gets giddy when he’s talking about practical Christian faith for average people. Francis Chan can’t stop challenging listeners to live more radically.

Like theological convictions, preachers can let their passions make them overly repetitive and, as a result, neglect other important issues. But passions are often a good gift of God that the preacher should not ignore.

Different Context

Most of the dynamics we’ve focused on for seeing where preaching styles come from relate to the preacher. But we can’t forget a major factor: context.

Where you are in the nation or world and who are the people that live there are major factors in shaping preaching style.

Tim Keller ministered for years in the heart of Manhattan, reaching highly educated white collar workers and cultural creatives. This context shapes not only Redeemer’s approach to church (they are more likely to have an orchestra than a rock band), it also shapes his preaching. Keller knows that his context requires intelligent, skillful communication that engages with art, literature, and academia.

Charlie Dates ministers on the south side of Chicago in a predominantly African-American community. This context evokes a call-and-response style of preaching that would leave many suburban white congregations confused. But it fits perfectly in his context.

Matt Chandler ministers in Dallas, the “buckle of the Bible belt.” So it’s not a surprise that he’s far more likely to confront the churched person than to appeal directly to the unchurched.

Wise and happy preachers often find a way of matching their makeup with their context, though some are able to fruitfully serve in a more “cross-cultural” way.

Different Vision

All of the above factors often lead to and connect with an overall vision for ministry that influences preaching. The pulpit is typically one of the strongest tools in a pastors’ toolkit for moving the congregation toward a preferred outcome.

Some preachers have a vision built around “doing anything short of sin” to win somebody to Jesus. Others are working to build up believers.

Some pastors’ vision involves inspiring people to action in the community. Others are working toward creating a passionately worshipping church.

Whether the specific vision relates to worship, evangelism, discipleship, fellowship, missions, racial reconciliation, or community development — the vision shapes the preaching style.

How to Find Your Preaching Voice

The sad reality is that too many young preachers simply adopt the voice of their favorite preachers or the tradition they came from. They assume that if they do what works for others it will work for them.

The danger in highlighting the styles of well-known preachers in an article like this is that you might be tempted to view it as a menu, where you simply try to combine the styles of preachers you like.

But God already has Bryan Loritts and Greg Laurie. He made you to be you.

What’s the path to finding your preaching voice?

1. Take Inventory.

How would your personality, spiritual gifts, experiences, theology, passions, context, and vision most naturally come through in your preaching?

Here are some questions to consider:

- Personality: How has God made me? What am I naturally good at and energized by? What might seem daunting to others but feels effortless to me? What am I like when I feel most comfortable in my own skin?

- Spiritual Gifts: Where do I tend to experience God’s greatest blessing on my ministry? What activities seem to have an extra anointing from God’s Spirit?

- Experiences: What was my life like before I met Jesus? What have been my most significant spiritual moments? What painful experiences have left their mark on me? What work or family experiences stand out as memorable?

- Theology: What aspects of core Christian theology most excite me? How clearly have I defined what I believe? What Bible passages hold an extra special place in my heart? What theological truths have made the biggest impact in my life? What theological errors am I especially afraid of?

- Passions: What do I daydream about? What areas of need in the world am I most drawn to? What issues light me up?

- Context: What are the people like that I’m trying to reach? What are their core concerns? What language do they speak that I need to learn? What idols do they revere that I need to challenge? What do these people see and experience that others may not?

- Vision: What do I hope God does through us? What is my dream for my church or ministry? Where are we trying to go? What do I hope to see happen through our efforts?

2. Get a ton of reps.

We began with Keller’s quote about your first 200 sermons being lousy. How do you overcome it? Tons of reps.

As a young preacher seeking to develop your voice, take every opportunity to speak or preach. Go to nursing homes, speak at high school FCA meetings, teach Sunday school, preach on Sundays — do anything you can to get reps.

3. Watch and listen to your sermons.

It’s painful.

Agonizing.

But it’s how you get better. Hearing and seeing yourself reveals important nuggets and allows you to notice improvement over time.

As you watch, pay attention to your particular filler words, habitual gestures, voice inflection, and physical presence. Ask yourself whether you sound like yourself or somebody else.

Notice the elements that feel the most like yourself and the ones that don’t.

4. Invite feedback from trusted mentors.

Reps are crucial. But evaluated reps are even better.

Just like a baseball player — even one who makes $20M per year — uses a coach to help him see what he can’t identify on his own, preachers need “coaches” who can point out what they need to hear.

Importantly, remember that somebody does not have to be a great preacher to be able to offer helpful preaching feedback. Often people who aren’t gifted preachers give tremendous feedback because they know what great preaching sounds like. Only a prideful fool would scorn their input.

One note of caution here: once people start listening critically to sermons to provide feedback, it’s hard for them to turn it off. Be careful of accidentally training many people to listen like judges on The Voice instead of like Christians who need God’s word.

5. Listen to a variety of preachers, but especially those whom you are not tempted to imitate.

As we’ve said, we can learn a lot from reflecting on other gifted preachers. So listen broadly and incorporate lessons that fit who you are.

At the same time, however, be careful about listening too much to preachers that you are tempted to imitate. Next thing you know, you’ll be saying, “You tracking with me?!” like Matt Chandler, “I wish I had somebody who was listening!” like Charlie Dates, or endlessly quoting C.S. Lewis like Tim Keller (OK, that one’s not so bad).

The more confident you become in your own voice, the more you’ll be able to listen to others without being tempted to rip off their style.

6. Be willing to try new things.

The way you discover anything is by experimentation.

Try different approaches to notes — manuscript, outline, notes-free. Try a pulpit or a table or a stool.

Try different lengths of sermons and different preparation processes.

Don’t be so afraid of imitation that you aren’t willing to try something that might really work for you.

7. Embrace your limits by resting in the gospel.

This may sound like the opposite of #6, but at some point you realize you have limits. You will likely never be like some of the preachers you most admire. That’s OK.

Rest in the gospel of Jesus. He’s the one who loved you and gave himself for you before you ever preached a sermon.

He’s been crazy about you since before the foundation of the world, and his affection for you doesn’t rise or fall on the basis of your preaching.

In his sovereign kindness, he is going to use the foolishness of your preaching to accomplish his purposes. And he’s going to grow you through the process. So rest in him.

Conclusion

We create products and resources for preachers because we want to help you be the best preacher you can be.

We believe that God has given you a distinct preaching style and we want to help you uncover it and use it for his glory.

Commit to expository preaching, figure out your preferred structure, and find your voice. Do it all in the power of the Spirit and watch what God will do.